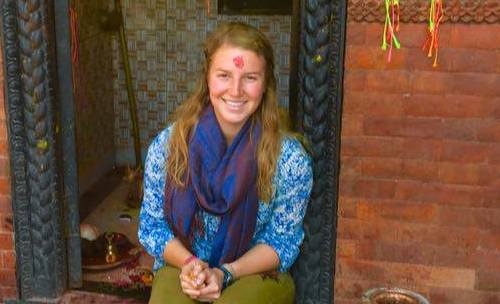

Sarah Kosling graduated from Denison in 2014, with a Bachelor of Science in biology. She was accepted into the Peace Corps program and traveled to Nepal in early 2015, but she returned to the United States due to a devastating earthquake. Kosling went back to Nepal three weeks later and continued her work as an agriculture volunteer working on Peace Corps’ Nepal Food Security project. This is an excerpt from her blog.

I now live in the Western Hills of Nepal, in a small village in the district of Arghakhachi. My closest fellow Peace Corps volunteer is a two-hour bus ride or one-day walk away. I’ve been here for almost nine months now, which is incredibly hard to believe.

As an agricultural volunteer, I teach the farmers (which is every Nepali) innovative agriculture techniques to improve dietary diversity and the amount of food available, and hopefully generate income. I’ve learned a lot about project sustainability and how difficult surveying a population can be.

The village is my office, and my job is getting out in the field and teaching. At times, it is really difficult to have so much freedom. As Americans, we have a great deal of structure from a young age.

Here’s what my day-to-day looks like. I live with my Nepali host family: my didi, “older sister,” who is 35; and two younger brothers, 13 and 15. Every morning my didi wakes up at around 6 a.m. to care for two buffalo, clean the house, lipnu (spread fresh red clay and buffalo dung on the dirt floor to repair the previous day’s wear and tear), and carry water from the dhara (water tap) to our house — jug by jug.

I wake up to help carry water and then go for a run. I never liked running hills before Nepal, but when they’re the only option, you learn to love them. After my run, I carry water into the enclosed outhouse toilet and take a cold bucket bath. They’re really fun in the winter.

Nepalis live off the land, only eating what they’ve grown. Therefore, our diet is lacking in diversity. Day in and day out, we eat the same thing — whatever’s in season. At around 10 a.m. we have our first meal of the day, consisting of rice, lentils, some variation of an overcooked, over-salted, oily vegetable. We eat this for every meal with slight variation, morning and night (only two meals a day in Nepal), every day. I have very vivid dreams about pizza and bagels with cream cheese.

I took for granted the simple things, like running water, a gas-burning stove (we cook over open fire here, and respiratory illness is the number one cause of death), constant electricity and central heating. And most of all, the relative equality in America across gender, race and ethnicity.

I get really fed up with the gender inequality here and have lost any filter I once possessed in the States. Women do approximately 75 percent of the work, while their husbands (with whom they have arranged marriages at 17 to 20 years old) go to an “office job” where they sit and visit with friends and get paid by the government. Or the men go abroad to work in India, Saudi Arabia, Qatar, Kuwait, etc., and leave everything behind for their wives to manage.

Nepal exists at a level of impoverishment most Westerners do not know. My Nepali family doesn’t have enough to give my brothers lunch money, so they last the entire school day, until 4 p.m., without eating anything after the morning meal.

Before I arrived at the site, some nights my Nepali family would go to bed hungry because they didn’t have enough rice from that year’s harvest. Most people have never driven a car, will never get their license, and are shocked when I tell them I can drive and have a car in the States. There is little infrastructure here, and development works at a snail’s pace.

But living here also has made me appreciate many things in Nepal that America lacks. Relationships are valued over material possessions, and family is everything. Grandmothers and grandfathers live with one of their sons and his family until the day they die, usually carrying their weight in manual labor. People die mostly of natural causes with little suffering.

Nepalis have a special relationship with nature because they’re always outside. They know the name of every plant and tree, how to climb a seemingly climbless tree, and exactly when it will rain without consulting the Weather Channel.

Joint Project with Granville Schools:

The three main goals of the Peace Corps are 1) to provide technical expertise and manpower to developing countries; 2) to share American culture with host country Nationals (Nepalis); and 3) to bring host country (Nepali) culture back to America.

Upon arrival in Nepal a year ago, I realized that, while Nepal is home to world-renowned trekking and is the land of Lord Buddha, it's also incredibly polluted. Trash litters the streets, streams and fields. Everywhere you look there is trash on the ground, even in rural Nepal where I live. There is no waste management system here, and Nepali habit is to dispose of waste by throwing it on the ground.

I am excited to begin a collaboration with my high school in Granville, doing a project that is in line with goals 2 and 3. I reached out to Granville High School teacher Mr. Reding and his Environmental Science class to work with me to help Nepalis with their trash disposal issues.

I will be working with Mr. Reding’s students to look at ways to recycle plastic bags, Ramen Noodle bags (which are everywhere), or different ways to introduce environmental education.

I plan to have Nepali students correspond to the students in Mr. Reding’s class in the States, and hopefully they will write back. The Nepalis would be ecstatic to receive this correspondence. I plan to work with my professors at Denison to introduce a similar program next year — stay tuned! This is one way to build bridges between cultures and to open students’ eyes in both cultures.